Tulsa Race Massacre: 100 years ago, a White mob torched 'Black Wall Street' and slaughtered Black residents

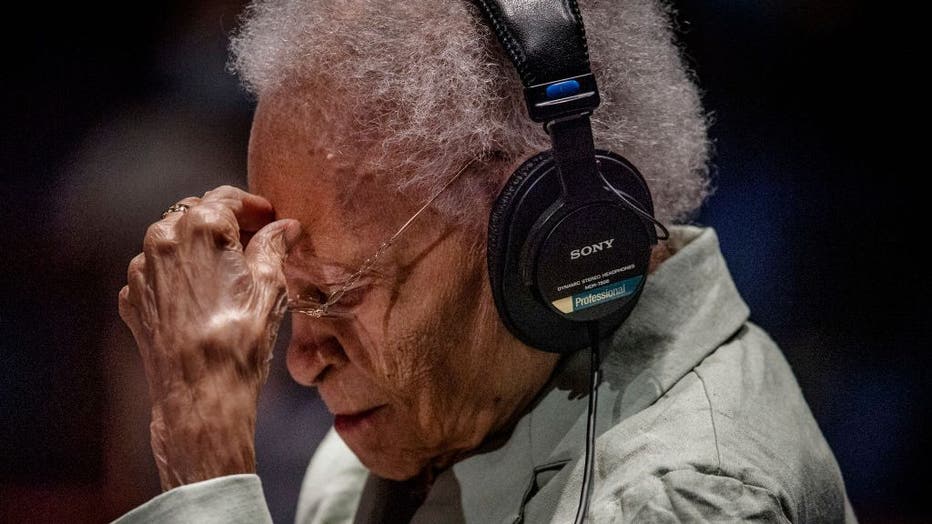

TULSA, Okla. - Viola Ford Fletcher has lived through two pandemics, two world wars, the Great Depression and segregation — and she still vividly remembers the night of May 31, 1921.

The House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties sat in silence on May 19 as the 107-year-old told them about the night an armed White mob came to Tulsa’s Greenwood District.

Fletcher, her younger brother, Hughes Van Ellis, and Lessie Benningfield Randle — the last known survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre — are still pursuing justice for what happened to them a century ago. The trio filed a lawsuit last year seeking reparations, FOX News reported.

Hughes Van Ellis (L), a Tulsa Race Massacre survivor and World War II veteran, and Viola Fletcher (2nd R), oldest living survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre, testify before the Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Subcommittee hearing on "Continuing Inju

Fletcher painted a vivid picture to the subcommittee of what she witnessed as a 7-year-old, saying she can still see Black men being shot and Black bodies lining the streets.

She can still smell the smoke and see the flames burning Black-owned businesses to the ground. She still hears airplanes flying overhead and the screams that never went away.

Somethings you just don’t forget, even if the country tried to make sure everybody else did.

"I have lived through the massacre every day," Fletcher told the committee. "Our country may forget this history, but I cannot, I will not and other survivors do not. And our descendants do not."

Before being rushed out of her family home, Fletcher remembers feeling rich when she went to bed on the night of the massacre. Not just rich in terms of wealth, but in culture and heritage.

"We had great neighbors and I had friends to play with. I felt safe. I had everything a child could need. I had a bright future ahead of me. Greenwood had given me a chance to truly make it in this country," Fletcher recalled. "Within a few hours, all of that was gone."

The Greenwood District

Greenwood came to be in 1906 in what was then Indian territory.

Some Black people who had been enslaved by Native American tribes were later integrated into tribal communities after emancipation.

Many of them went on to purchase land in what would become Greenwood through the Dawes Act, which allowed for the purchase of tribal lands. And many Black sharecroppers fleeing racial oppression from the Jim Crow south flocked to the area, especially after Oklahoma’s oil industries proved lucrative.

Oklahoma became increasingly racist after achieving statehood in 1907, according to the History Channel. Jim Crow laws rendered life in Tulsa similar to life in the south.

With the city divided by segregation and a railroad track, Black people banded together in a section of town purchased by O.W. Gurley — a wealthy Black landowner.

He named the area Greenwood and opened a boarding house for Black people. Other entrepreneurs, like J.B. Stradford, soon moved into the district — as did Black people just searching for better opportunities.

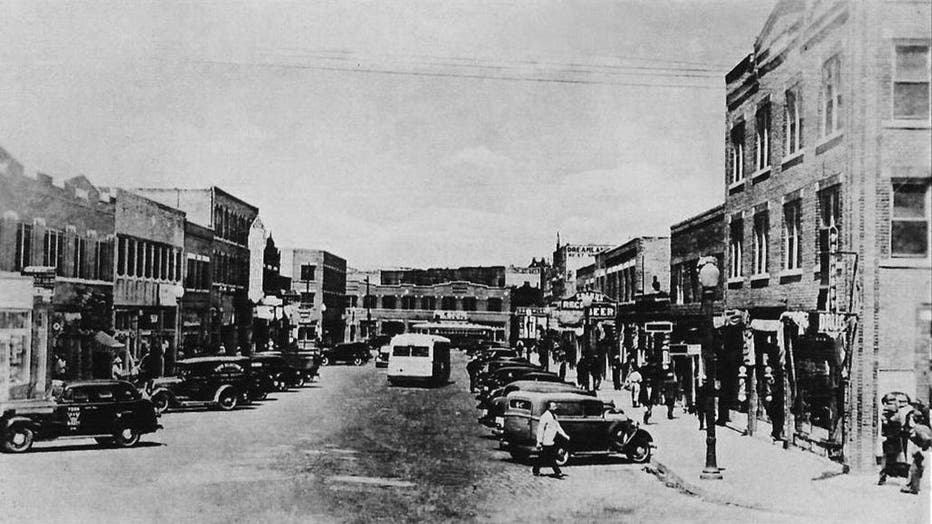

According to Dr. Kristen Oertel, the chairperson of the Department of History at the University of Tulsa, White Tulsans would mock Greenwood as "Little Africa." But Black Tulsans had another name for it: Black Wall Street.

"Black Wall Street describes it more accurately because it was a thriving business district anchored by Greenwood Avenue and dozens of Black-owned businesses, schools, theaters, lawyers’ offices, dentists, doctors," Oertel explained.

The "Black Wall Street" sign is seen during the Juneteenth celebration in the Greenwood District on June 19, 2020 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. (Photo by Michael B. Thomas/Getty Images)

Black Tulsans kept their money in Greenwood, allowing its businesses and residents to flourish. This went beyond living comfortably. Greenwood was one of the most affluent African-American neighborhoods in the country.

"It was a self-contained, incredibly rich – both economically and culturally – region in the middle of Oklahoma," Oertel said.

Less affluent families also lived in the district. They often worked lower-paying jobs on the White side of Tulsa. But the money they earned was exclusively spent in Greenwood, causing a great deal of resentment and jealousy in the White community.

One of the Black men working on the White side of town was named Dick Rowland. He shined shoes in a White-owned parlor downtown.

Black people weren’t allowed to use the restroom inside the parlor where Rowland worked. If Black employees ever needed to relieve themselves, the parlor owner had arranged access to a "colored" bathroom on the top floor of the nearby Drexel Building.

Drexel Building incident

On May 30, 1921, Rowland stumbled while entering the elevator of the Drexel Building, bushing the arm of the White 17-year-old operator named Sarah Page.

Page screamed, which caused Rowland to sprint out of the elevator.

Oertel described the incident as minor in modern terms. By most accounts, this was accidental physical contact.

But that wasn’t the narrative floated around town. Oertel said the story quickly exploded into that an African-American man had assaulted a White woman. Some went so far as to accused Rowland of attempted rape.

"In that 1920s context of American history, that accusation of rape by Black men was commonly used to justify racial violence against Black communities," Oertel said.

Authorities arrested Rowland and held him at the courthouse downtown. The Tulsa Tribune published stories headlined "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator" and "To Lynch Negro Tonight."

At this point, the Black community began to mobilize — fearing for Rowland’s life.

"They know from the minute the accusation occurs, that he’s vulnerable to lynching," Oertel said. "Lynching is common at this point in time."

View of along Greenwood Avenue, Tulsa, Oklahoma, early twentieth century. (Photo by Greenwood Cultural Center/Getty Images)

On May 31, a group of Black men, many of them World War I veterans, surrounded the courthouse. A White mob showed up, "ready to kidnap Rowland basically and take him away and lynch him," Oertel said.

According to an online exhibit at the University of Tulsa, the two groups engaged in a verbal altercation while the Black group was filing out of the area. One of the White men saw a Black veteran with an Army-issued revolver.

"N*****, what are you doing with that pistol?" the White man asked. The Black man responded, "I’m going to use it if I need to."

"No, you give it to me," the White man demanded as he tried to disarm the Black man. "Like hell I will," the black man replied.

When the gun discharged, both sides opened fire and people started dying.

The violence spilled onto the streets of Tulsa. As Black people retreated to Greenwood, the White mob grew in numbers.

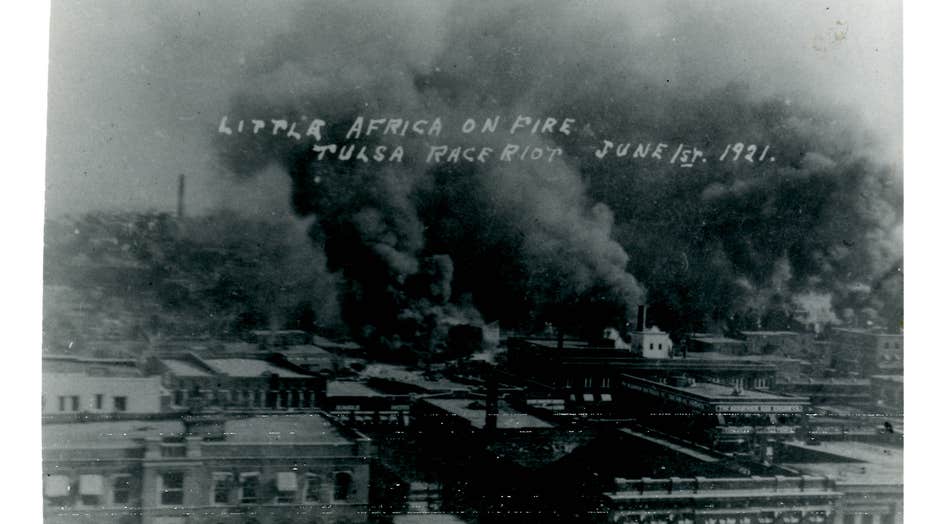

Buildings in the Greenwood District burning with smoke-filled sky as viewed towards the west from Frankfort and Hartford streets from the Tulsa Race Riot, 1921. Inscribed on the front: "Little Africa on fire, Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921." (Courte

Civil officials deputized several White men, providing them firearms and ammunition and directing them towards Greenwood.

"The White community is emboldened by the sheriff’s department’s encouragement, basically, to attack Greenwood," Oertel explained, "to attack this thriving Black community and burn it to the ground."

The Massacre

Thousands of armed White men moved into Greenwood gunning Black people down in the street.

It no longer mattered if you were among the Black men trying to save Rowland at the courthouse. According to the Tulsa Historical Society Museum, families were ripped from their homes while White people looted all of their valuables.

The mob moved from house to house, business to business, looting and shooting. Witnesses claimed that gunfire and firebombs rained down from airplanes flying overhead, the Oklahoma Historical Society said.

Very little was spared. Smoke billowed high into the night sky as the mob burned shops, restaurants, theaters, hospitals, schools, churches, homes and hotels.

Mount Zion Baptist Church burning as heavy smoke is visible from the roof, Easton Street and Elgin Avenue. (Courtesy of the OSU-Tulsa Library Special Collections.)

"It was like a war," 106-year-old Randle explained to the subcommittee. "White men with guns came and destroyed my community. We couldn’t understand why. What did we do to them? We didn’t understand. We were just living, but they came and they destroyed everything."

When firefighters tried to put out the blaze, the mobs interfered. But help arrived when Gov. James B. A. Robertson declared martial law and sent in the National Guard.

While some troops helped firefighters put out the flames, others went about imprisoning all Black Tulsans who had not already been apprehended by vigilantes. They only gained their freedom if they were vouched for by a White person who accepted responsibility for the Black person’s subsequent actions.

More than 6,000 people were held at the Convention Hall and Fair Grounds for up to eight days.

Houses on fire with a smoked-filled sky from the Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921. Photograph by Arthur Dudley. (Courtesy of the OSU-Tulsa Library Special Collections.)

By the time order had been restored, 35 city blocks laid in ruin and more than 1,200 homes had been destroyed. The cost of property damage is estimated to have been $1.5 million in real estate and $750,000 in personal property, which is equal to more than $30 million today.

The official death count is still recorded as 36 to this day. But historians have concluded the true death toll was drastically undercounted.

They now believe more than 300 people lost their lives in the carnage.

Randle said survivors were told many bodies had been dumped into a local river. Others were interred in mass graves that are still being searched for to this day.

Aftermath

Many Black people fled Tulsa and never returned. The ones who did found themselves with nothing.

"They literally were sitting in ashes, stunned by what had just occurred in 48 hours," Oertel said. "Their homes, their businesses, their livelihoods went up in flames. Their family members were killed."

Remnants of burned to the ground buildings in the Greenwood Community from the Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921. (Courtesy of the OSU-Tulsa Library Special Collections.)

Many of the White officials declined aid from outside of Tulsa, leaving the now virtually homeless Black population fewer resources to rebuild.

And because authorities labeled the incident a riot, insurance companies were able to decline coverage to Black survivors.

The Tulsa Historical Society Museum notes some White Tulsans lent a helping hand to their Black neighbors. But nobody was as much help as the American Red Cross, who remained in the area for months after the massacre.

In the decades that followed, Greenwood rebuilt to some version of what it was before. By the 1940s, even more Black businesses thrived than what had been open in 1921.

Oertel said Greenwood has always shown incredible resilience, though it could not sustain its success after desegregation allowed those once-isolated Black dollars to be spent outside of the district. And eminent domain paved the way for a highway that divided the district.

Greenwood’s renaissance did little to stop the generational trauma faced by many survivors.

Fletcher told the subcommittee the destruction robbed her of the chance to attend school beyond the fourth grade — which limited her earning potential and caused her to spend most of her life as a domestic worker serving White families.

To this day, she struggles to afford her everyday needs.

Tulsa Race Massacre survivor Viola Fletcher listens to fellow survivor Hughes Van Ellis during the House hearing on the Continuing Injustice: The Centennial of the Tulsa-Greenwood Race Massacre Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civi

"I have never made much money — and my country, state and city took a lot from me," Fletcher said. "Despite this, I spent time supporting the war effort in the shipyards of California."

Indeed, Van Ellis too contributed to America’s World War II effort, serving in the Army in an all-Black battalion in the Far East.

Van Ellis, 100, told the subcommittee that the massacre left him with a hard childhood. His family didn’t have much. And what little they did possess, they worried it would be stolen — as had been the case in Greenwood.

"You may have been taught that when something is stolen from you, you can go to the courts to be made whole. You can go to the courts to get justice. This wasn’t the case for us," Van Ellis explained. "The courts in Oklahoma wouldn’t hear us. The federal courts said we were too late. We were made to feel that our struggle was unworthy of justice, that we were less than the Whites, that we weren't fully Americans."

None of the crimes committed in the massacre were ever prosecuted or punished by governments at any level. And neither was Rowland for the incident that sparked the entire ordeal.

In September 1921, authorities dismissed the case against Rowland after Page declined to pursue charges.

Legacy

For many people, their introduction to the Tulsa Race Massacre comes outside of academic settings. Even scholars like Oertel have similar experiences.

"I was a history major in college. I went on to a graduate degree. I did not learn about the race massacre until graduate school in a class on African-American history," Oertel explained. "It wasn’t even an American history class. It was focused on African-American history."

Oertel said when she first arrived at the University of Tulsa in 2010, she had students from Booker T. Washington High School, a predominantly Black school that survived the massacre, who had not been taught about it.

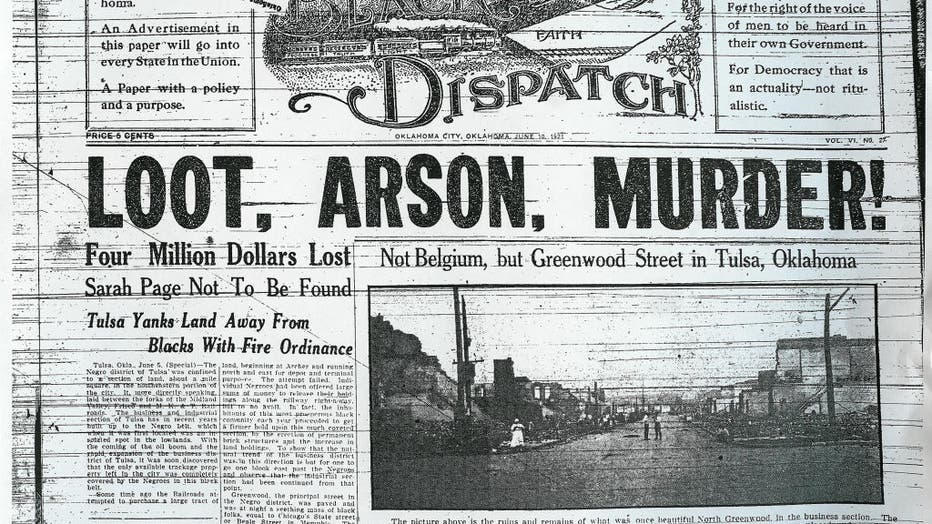

Newspapers covered the aftermath of the massacre extensively. Oertel said she’s seen articles about it from outlets in St. Louis, Kansas City and even New York.

"America, and especially Black-American newspapers, were well aware of the destruction that occurred," Oretel said, adding that it’s all the more remarkable that news about this was silenced for decades.

View of the front page of an edition of the Black Dispatch newspaper, detailing incidents of the Tulsa Race Massacre (which occurred the previous week), Oklahoma, June 10, 1921. (Photo by Greenwood Cultural Center/Getty Images)

Many of the local newspaper articles were destroyed. As detailed in the archives at the Tulsa Historical Society Museum, many of the photos we have today still exist because they were printed on postcards.

For decades, the shroud of secrecy threatened to be the legacy of the massacre, but Oertel said that is changing. She’s noticing more students already familiar with it and she said there’s been an effort to reclassify what happened to Greenwood as a massacre, not a riot.

"I think the word riot often has a connotation of radical Black Americans causing trouble. This is not what happened," Oertel stressed. "This was a threatened lynching of a Black man by a White mob that instigates racial conflict and explodes into a massacre of not just Black bodies, but Black property, Black generational wealth."

Burned ruins of residences in the Greenwood Community showing remnants of several metal bed frames from the Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921. (Courtesy of the OSU-Tulsa Library Special Collections.)

Oertel said the massacre’s centennial has placed a spotlight on Black Wall Street and played a major role in educating today’s Americans about Oklahoma’s 20th-century tragedy.

A new museum and memorial, Greenwood Rising, will open its doors this summer. And Tulsa’s Centennial Commission has spent years planning programs, projects, events and activities to commemorate the anniversary.

The Remember & Rise ceremony will feature a performance from decorated singer John Legend and politician Stacy Abrams will deliver the keynote address.

But after the 100-year commemoration passes, the survivors and their descendants will continue their fight for reparations. Though the perpetrators of these crimes have likely all died, the surviving victims are still seeking justice.

Fletcher and Randle take issue with the centennial commission fundraising off their trauma and not sharing the money with the survivors.

"They have raised more than $30 million and have refused to share any of it with me or the other two survivors," Randle testified. "They have used my name to further their fundraising goals without my permission and misrepresented my support of their upcoming centennial events focused on making Tulsa look good and not justice."

Van Ellis pleaded with the committee not to let him "leave this earth without justice like all the other massacre survivors." Even though his wait has been long, it has done little to dull his faith in America — as neither the massacre, segregation nor the denial of the benefits he was entitled to under the G.I. Bill did.

Hughes Van Ellis, a Tulsa Race Massacre survivor and World War II veteran, testifies before the Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Subcommittee hearing on "Continuing Injustice: The Centennial of the Tulsa-Greenwood Race Massacre" on Capitol Hill in Wa

"I still believe in America," Van Ellis said, still proudly wearing his U.S. Army hat. "I still believe in the ideals I fought overseas to defend."

As they did when the other survivors finished speaking, the subcommittee stood and applauded Van Ellis for his testimony and service.

When asked if he wanted to say anything else, Van Ellis offered a parting message:

"I want to say I appreciate being here, and I hope we all can work together. We are one," Van Ellis said, holding up a single finger. "We are one."

This story was reported from Atlanta.