The Up Stairs Lounge fire: How a deadly attack on the gay community fueled lasting change

A priest prays for the victims of the Up Stairs Lounge arson June 24, 1973. (Photo by G.E. Arnold, Times-Picayune archive)

NEW ORLEANS - This weekend marks 50 years since the deadliest fire in New Orleans history ripped through a French Quarter gay bar, killing 32 people.

The Up Stairs Lounge arson is the second deadliest attack on gay people in U.S. history, surpassed in 2016 by the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando.

No one was ever charged in connection with the massacre; the man believed to have started the fire took his own life in 1974. But as author Robert Fieseler explains, finding "the enemy" in this tragedy is more nuanced than it sounds – and the gay rights movement it fueled continues half a century later.

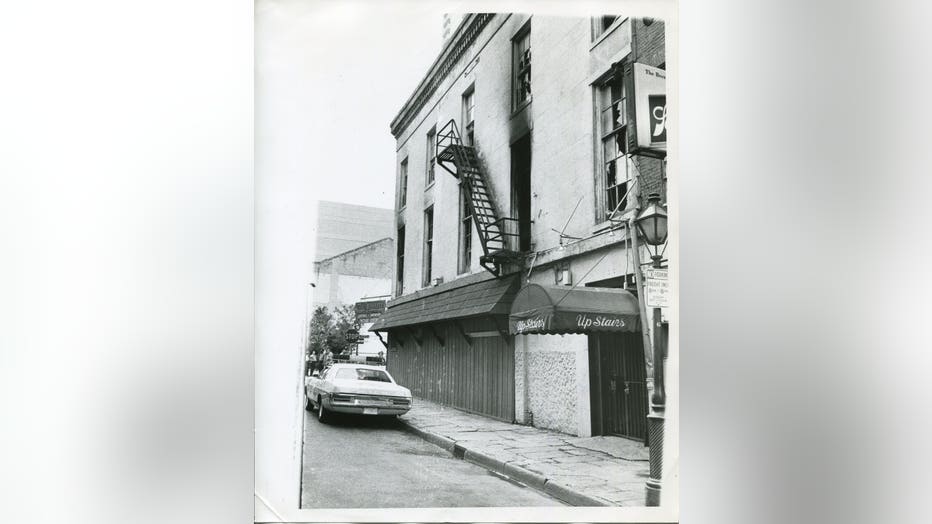

The Up Stairs Lounge (Times-Picayune archive)

"I thought this was a standard true crime story," said Fieseler, author of Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation.

"I thought I was going to figure out that there was someone who hated the Up Stairs Lounge patrons and was overtly homophobic who'd committed a hate crime," he said. "And I instead discovered a much messier situation."

June 24, 1973

The Up Stairs Lounge (Photo by Ralph Uribe, Times-Picayune archives)

It was a Sunday in the famed French Quarter. On its edges, the "downlow" queer capital of the South was celebrating the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising in New York City.

At the time, New Orleans was known as a place where people could run away and live a "a carefully curated, semi closeted existence," Fieseler said.

"Queer folk in the ‘70s lived in the social compact," Fieseler said. "You can engage in any kind of private social behavior you want as long as you don’t identify it as gay or queer. If you did in the ‘70s it would lead to police violence and losing your job and home."

At the working class Up Stairs Lounge, the bar was full of patrons taking advantage of the day’s drink special: $1 for two hours of unlimited draft beers.

When the fire started that night, many of the victims were trapped behind barred windows. Others died in a stampede while trying to escape. In all, 32 people lost their lives.

The Up Stairs Lounge fire aftermath June 24, 1973. (Times-Picayune archives)

Johnny Townsend, who interviewed more than 30 people who survived the fire for a book that he published in 2011, wrote that one survivor overheard two firefighters talking while the fire still roared.

One was frustrated that he couldn’t get up to the blaze, Townsend wrote. The other replied, using a slur for homosexuals, "Let ’em burn."

Earlier in the day, a man named Roger Dale Nunez was ejected from the bar for being belligerent and harassing customers, screaming "I'm going to burn this place to the ground!" as he was thrown out.

Fieseler said he was later seen at a store near the bar buying a can of lighter fluid – the same size and brand of lighter fluid found emptied on the staircase of the Up Stairs Lounge.

But Nunez himself was not an outwardly homphobic vigilante: he was an "internally conflicted" gay sex worker, Fieseler said, "who was intensely conflicted due to religious and cultural reasons about his own same-sex desires."

"And he was a person who struggled to occupy a place even in an accepting community like the Up Stairs Lounge."

Nunez was never charged and took his own life eight months after the fire.

The aftermath

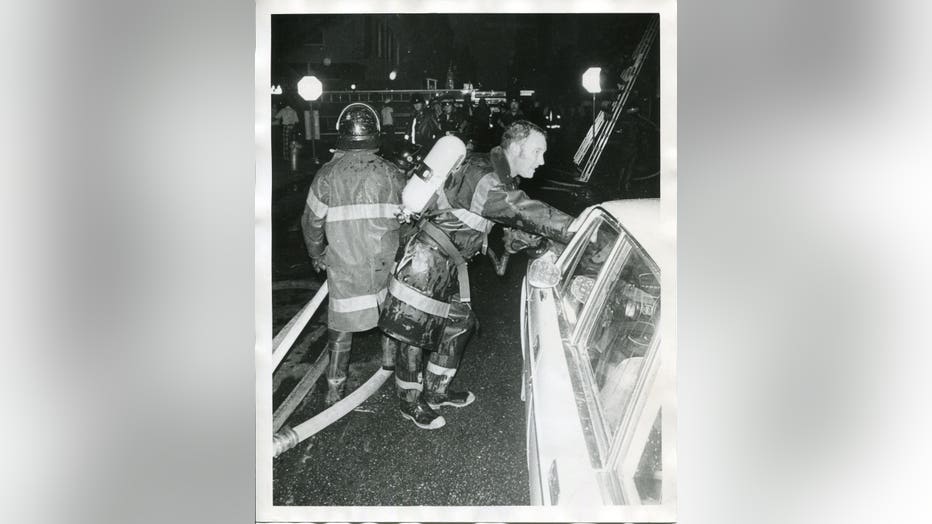

First responders treat victims of the Up Stairs Lounge arson June 24, 1973 (Times-Picayune archives)

In the days following the city’s most lethal fire on record, the mayor of New Orleans was silent. Fieseler said he waited weeks to address the tragedy publicly – and only after he was pressed to do so. Former Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards never issued a statement of sympathy.

Reactions from the victims’ families were "extremely varied," Fieseler explained.

Some families, although they didn’t agree with the lifestyle, stepped up to claim the bodies. One of the victim’s families tried to have a funeral at a local Catholic church, but they were denied.

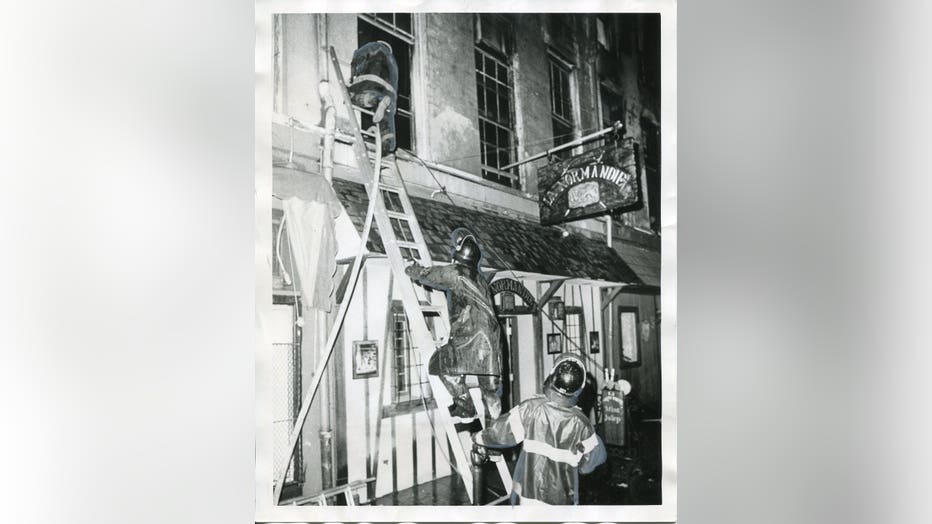

Firefighters at the Up Stairs Lounge June 24, 1973 (Photo by Philip Ames, Times-Picayune archive)

Others, like the family of Bill Larson, declined to accept his remains because his mother "feared backlash for her, for the circumstances of her son's death and for the way he'd chosen to live his life."

"She gave permission for the local mosque church to do so," Fieseler said. "I think that’s probably one of the harsher things to hear about, like a mother in death was so ashamed of her son she didn't want what was left of him."

Even the reaction from the gay community was complicated, Fieseler said.

At the time, the "gay elites" of New Orleans, who were surprisingly intertwined with city officials, tried to keep the arson out of the spotlight to avoid "further outing the gay underworld of the French Quarter."

"They feared if the social compact between semi closeted queers and the rest of society ended, that there would be much more police violence and things would be even worse for local gays," Fieseler said.

The movement

The history of June being Pride Month

Every June, the LGBTQ+ community and allies celebrate what has become "Pride Month."

Hours after the Up Stairs Lounge fire happened, national gay leaders from coast to coast decided to fly to New Orleans "to help triage and minister to a grieving community."

The leaders formed what was called the National New Orleans Emergency Task Force, held press conferences about the fire’s aftermath, and found a French Quarter church willing to hold a large memorial for the victims.

READ MORE: 3 out of 4 Americans support LGBTQ ad campaigns, GLAAD survey finds

Fieseler said 300 mourners packed into St. Mark’s Methodist, a prominent civil rights church on Rampart Street. They were promised there would be no cameras, but when TV crews ended up parked outside, panic ensued.

"And then a lesbian in the balcony stands up and says, ‘I came in through the front door, and I'm damn well going out that way,’" Fieseler said. "And so then she starts marching, and the entire crowd stands up and cheers and marches with her, out the front door of St Mark's Church into the camera. And they out themselves to the world."

Firefighters battle arson at Up Stairs Lounge on June 24, 1973. (Times-Picayune archives)

It was an "incredible, liberating moment," Fieseler said, and one that inspired political action. The gay community spent the ‘80s fighting for legislation to protect themselves from police violence and other atrocities they faced.

In 1991, the New Orleans City Council passed an anti-discrimination ordinance protecting sexual orientation in the city.

"So we're talking like a full 12 years before the Supreme Court, in Lawrence V. Texas, strikes down anti-sodomy laws, which essentially allowed legalized discrimination against queer folk nationally," Fieseler said. "And you have New Orleans, a full 12 years before that, stating that the city will be an oasis city for individuals who are non-heterosexual."

Last year, the New Orleans City Council passed a resolution formally apologizing for the role the city played in the tragedy, and directing city officials to work on identifying the few victims who are still unnamed.

"The fire was the catalyst for the anger that brought us all to the table," Charlene Snyder, who owned a popular lesbian bar, told Fieseler.