Studies find winter is fastest-warming season in Philadelphia; here's why that's bad news

Winter Outlook 2021-2022: Below average snowfall totals expected for Delaware Valley

The FOX 29 Weather Authority is getting you ready for winter weather with its highly anticipated winter outlook.

PHILADELPHIA - Tuesday marks the first day of winter in the Northern Hemisphere, but a pair of recent studies found winters in Philadelphia are warming faster than any other season. Although that means temperatures might be more tolerable, it's actually bad news for a number of reasons.

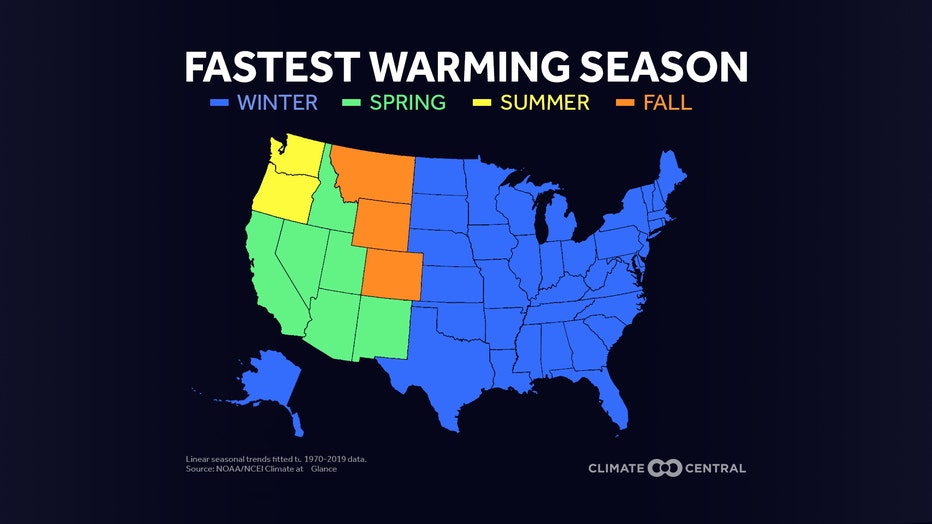

A study published in 2020 by independent research group Climate Central showed that, over the past 50 years, average temperatures increased more in the winter than in any other season for 38 of the 49 states in the continental U.S. Winter is defined as the three-month period from December through February.

Winter is the fastest-warming season for every state from the Plains to the East Coast, or just over 75% of the nation. This includes Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Climate Central noted all 49 states in the continental U.S. recorded an increase in average winter temperatures of at least 1 degree, and 70% of states recorded wintertime increases of at least 3 degrees since 1970.

Each color depicts which season has warmed the fastest since 1970. Winter is the fastest-warming season for the 38 states shaded in blue, including Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. (Map: Climate Central, Data: NOAA/NCEI)

"Warming winters may sound great at first, but they can have negative impacts on our health and regional economies," Climate Central said in a second study published last month, citing migrating pests, less snow and ice for winter recreation, a reduced water supply and lower fruit yields.

- Migrating pests: Mosquitoes and ticks will be able to migrate and survive in regions that were previously too cold to inhabit, bringing an increased risk of diseases such as West Nile Virus, Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) and Lyme disease.

- Less snow and ice: Winter recreation is a billion-dollar industry. Without enough snow and ice for skiing, ice fishing or snowmobiling, the industry could take a substantial economic hit.

- Reduced water supply: The West relies on a melting snowpack in the spring to help refill reservoir levels and irrigate crops ahead of the summer dry season. Warmer winter temperatures would likely result in a reduced snowpack to replenish the region's water supply.

- Lower fruit yields: Cold winter temperatures are required for cherry, apple and peach trees in order for them to develop fruit in the subsequent spring and summer months. Warmer winters could eventually limit fruit development.

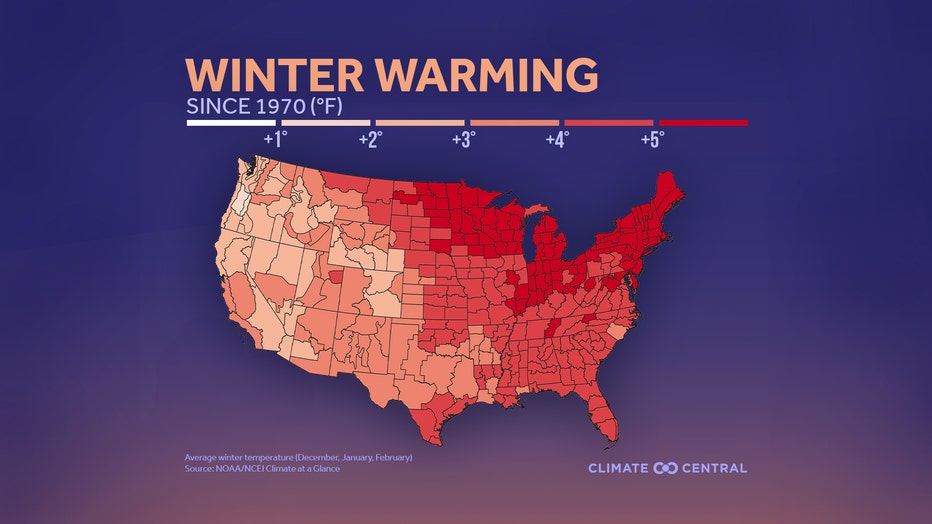

After examining data for 246 locations across the U.S., this second study found the region from the Great Lakes to the Northeast experienced the largest increase in average winter temperatures since 1970, specifically the cities of Burlington, Vermont (7.2 degrees), Concord, New Hampshire (6 degrees), Milwaukee (6 degrees), Chattanooga, Tennessee (5.8 degrees), and Green Bay, Wisconsin (5.8 degrees).

This map analyzes the magnitude of warming during the winter months (December-February) using 52 years of temperature data (1970-2021). (Map: Climate Central, Data: NOAA/NCEI)

About 98% (241) of the 246 locations in the study showed an increase in their average winter temperatures since 1970, with 202 of those 241 locations warming by at least 2 degrees between December and February.

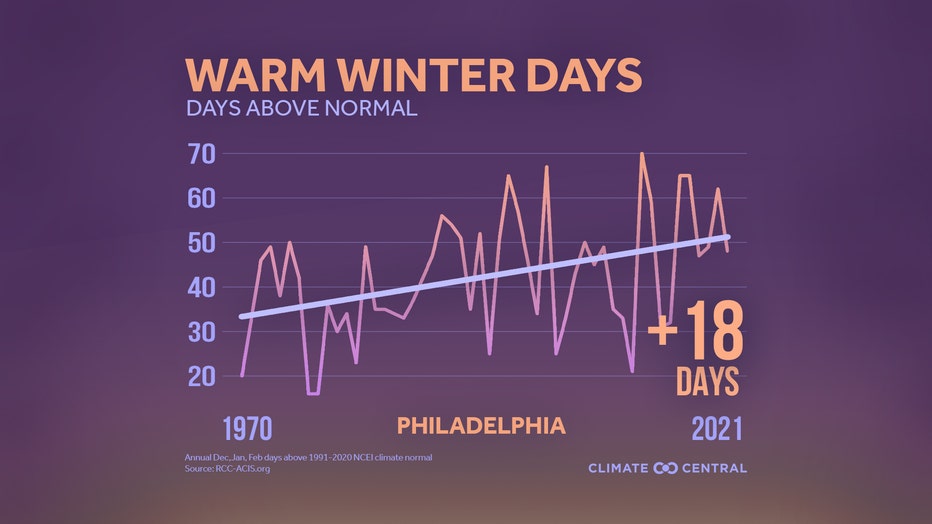

Climate Central also found nearly three-quarters (183) of the locations analyzed had at least seven more winter days with above-average temperatures than in 1970.

Philadelphia has 18 more winter days that are warmer than average when compared to 1970, while Atlantic City has 14 more such days, Allentown has 13 more and Wilmington has 11 more.

Philadelphia has 18 more winter (December-February) days that are warmer than average (1991-2020) when compared to 1970. (Graph: Climate Central, Data: NOAA/NCEI)

Although the long-term trend for most of the U.S. is an increase in wintertime temperatures, you can see from the graph above that there are year-to-year fluctuations, so some winters will be warmer while others will be colder.

"There can still be cold winters under climate change," Climate Central said in last month's study. "The likelihood of extreme cold conditions in a warming world is decreasing, but it is not zero. Some locations will still experience extreme cold or cold records – just not as cold or for as long as in the past."

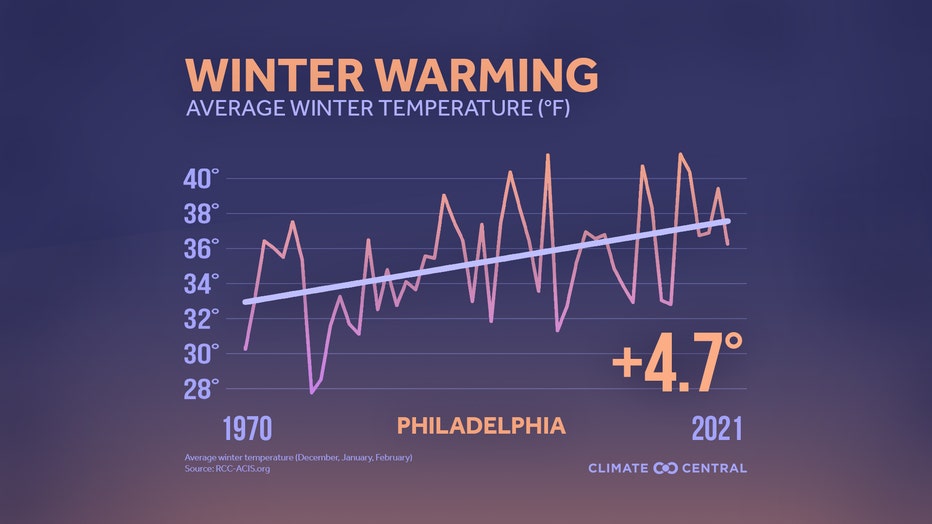

Average winter temperatures in Philadelphia have risen by 4.7 degrees since 1970, when December-to-February temperatures averaged about 33 degrees. Today, the city's temperatures average closer to 38 degrees during the coldest three months of the year.

Average winter temperatures (December-February) in Philadelphia are 4.7 degrees warmer than the same three-month period in 1970. (Graph: Climate Central, Data: NOAA/NCEI)